Would you like to spray on a potion that will make you instantly irresistible? Would you like everyone who gets a whiff of you to quiver with lust? Would you like to have an unfair advantage on the pull? Help is here! There are pheromone sprays which will do just that – fragrances and body sprays which will send people wild around you. Everyone knows that androstenone, androstenol, androstadienone, and estratetraenol are human pheromones and adding them to products produces very special effects.

Would you like to spray on a potion that will make you instantly irresistible? Would you like everyone who gets a whiff of you to quiver with lust? Would you like to have an unfair advantage on the pull? Help is here! There are pheromone sprays which will do just that – fragrances and body sprays which will send people wild around you. Everyone knows that androstenone, androstenol, androstadienone, and estratetraenol are human pheromones and adding them to products produces very special effects.

Except, of course, all of the above is probably rubbish.

There are many products on the market which claim to contain human pheromones. More than that – there are research papers, books and scholarly articles talking about putative human pheromones as though they had been identified.

Amazingly, every one of these products, articles, books, papers and claims is based on dodgy science.

There are no real ‘putative human pheromones’, as they are currently presented. However, since we’re mammals, it’s highly likely we do have them.

Very early on in human pheromone studies, something peculiar happened to thwart the research, and we may have been chasing the wrong leads ever since.

Doctor Tristram Wyatt from Department of Zoology, University of Oxford thinks that we should start again. I recently attended his excellent talk at the Royal Society of Chemistry (a version of which you can watch on TED and was written up as a recent Proceedings of the Royal Society B paper) in which he systematically demonstrated that a) it’s likely that we do have pheromones; b) no solid evidence exists for what they might be; c) the research into this area is under-funded and based on dodgy science; d) it would be great if we could start again, as though human beings were a newly discovered species.

Why should we forget everything we think we know and start from scratch?

Because we’re animals, we give off hundreds of odours just by being. Other animals have pheromones and it’s likely that we have them, too. While we don’t have a functioning vomeronasal organ (it does develop in-utero but regresses) this is not a problem as we now know that pheromones are detected by the main olfactory system in many mammals such as sheep. However, smells play a very big role in our lives and especially in sexual selection. The mechanisms for this are still quite fuzzy and hotly contested. We simply don’t understand just how much of human sexual behaviour is influenced by smell and what the pathways and biological processes are. We know that we’re highly influenced by our experiences, emotions and context, and while there have been some studies on the so-called ‘putative human pheromones’ which seem to demonstrate pheromone-like effects, no clear evidence exists to show how they are supposed to work in humans.

It’s clear that human beings give off, and react to odours – but it’s important to realise that not all odours are pheromones, and that we don’t know much about human pheromones at this stage.

Our personal body odour fingerprint has been found to influence mate selection. We seem to prefer the smell of partners whose immune system gene expression differs from our own (with the biological benefit being that if offspring are produced, their immune systems will express genes from both partners and therefore be stronger). Immunotypes from both partners would be incorporated into the offspring. It’s also been shown that women on the oral contraceptive pill can prefer the odour of partners whose immune genes are similar to their own (and subsequently experience a loss of sexual attraction to the partner they chose whilst on the pill when they come off the pill to try to conceive!). I attended a fascinating talk by Professor Craig Roberts about this topic a few years ago and it’s very interesting to think about how our natural body odour affects our fragrance selection – we’re better off wearing scents which we are instinctively drawn to because they are most likely to be the ones which enhance our natural body odour.

According to Dr. Wyatt, “We do seem to be obsessed by body odour – billions of dollars are spent on removing it and putting it back on again.”

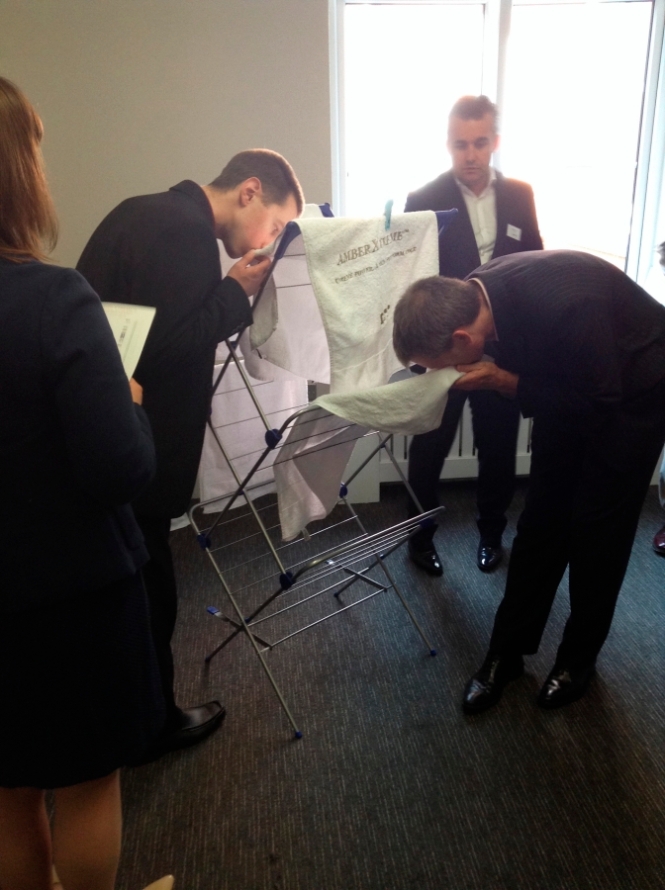

There are so-called ‘pheromone parties’ which should really be re-named to major histocompatability complex parties, but that wouldn’t sound nearly as sexy. Participants wear a t-shirt for a while before the party, place it inside a plastic bag, and the bags are given numbers. The t-shirts are sniffed by other partygoers and if they like the smell, a photo of them is taken with the bag and displayed on a screen during the party.

Of course human pheromones could also be at play here, but we genuinely have no clue yet what those might be.

What are pheromones?

- Pheromones are a chemical signal between members of the same species.

- They are same across the same species (e.g. all males of the same species, but possibly appearing in different amounts).

- They are usually a combination of molecules and can be short-range.

The first pheromone was identified in the Bombyx mori silk moth in 1959 by Adolf Butenandt & team. It was named Bombykol after the moth. In Dr. Wyatt’s opinion, the way in which this research was conducted represents a gold standard for pheromone identification and should be followed in other similar studies.

The criteria for identifying a real pheromone should be:

- To isolate a specific compound or a mixture of compounds (all compounds in the mixture should be necessary)

- There should be a clearly identifiable response to the pheromone(s) (in the Bombyx mori, scientists observed increased wing fluttering of the male moth in the presence of bombykol)

- Synthetic compounds should elicit the same response as real pheromones

- Realistic concentrations must be used in experiments

- There must be a credible pathway for evolution

We should expect humans to have pheromones because other animals do, too. Pigs, mice; rabbits all have them.

Humans can distinguish between a trillion different smells and though we might not rely on our sense of smell quite as much as some other animals, it’s wrong to think of our sense of smell as insignificant.

So what’s wrong with ‘putative human pheromones’?

There is simply no evidence for them.

The history of putative human pheromones can be traced back to the discovery of ‘copulins’ in monkeys (1970), and the idea of ‘menstrual synchronicity’ which was put forward in 1971 (the menstrual synchronicity thing is not proven, though – and looks like it might not be real). Androsterone and androstenal was discovered and researched in pigs around 1970-1980.

In 1991, a symposium sponsored by the Erox Corporation was held in Paris and many leading scientists were invited to attend. Slotted into the procedings was a paper about ‘putative human pheromones’ which also claimed that humans have a functioning vomeronasal organ: “Effect of putative pheromones on the electrical activity of the human vomeronasal organ and olfactory epithelium”. Erox Corporation had supplied the ‘putative human pheromones’ androstadienone (AND) and estratetraenol (EST) for the study, and had a clear interest in patenting them.

However, the study has no details of how these molecules were extracted, indentified, bioassayed and supposedly shown to be human pheromones.

In 2000, Jacob and McClintock published a paper “Psychological state and mood effects of steroidal chemosignals in women and men” and used the same ‘putative human pheromones’ in their experiments. This gave the putative human pheromone myth credibility.

Since 2000, there have been more than 40 studies (about 4-5 a year) using androstadienone and/or estratetraenol and these studies have been cited hundreds of times.

How is this possible? Aren’t we supposed to be evidence-based? One of the toughest things about researching human pheromones is the identification and extraction of them. So since it’s easy to purchase AND and EST, researchers seem to default to these. The literature has become self-referential which creates a closed loop of evidence. It’s easy to confuse the volume of work with quality, and in this case there is no lack of literature – just a lack of original evidence. In fact, it is now a commonly held assumption that there really are ‘putative human pheromones’, but nobody seems to have looked at the 1991 source critically.

All fields in science also suffer from positive publication bias (where only positive studies are published and negative ones are not). The worst area for this is psychology, at about 90% of the published work being positive. Since the research into human pheromones falls into this field, and since there have been no Bombykol ‘gold standard’ studies, everything we have on the ‘putative human pheromones’ seems to ultimately rest upon the original rather questionable study.

Now what?

According to Dr. Wyatt, we should approach human pheromone study as though we were a newly discovered species. We should look for ways in which to identify and bioassay pheromones – and he thinks that there might be something in how human babies seem to recognise the odour of their mothers. More importantly, when the scent produced by special glands on the areolas of lactating mothers has been collected and presented to babies, they react to the smell by starting to suck even if the scent was not from their own mother. There could be a mammary pheromone at play. Other things we could do is to compare people pre- and post puberty, but the main problem with all of this is how much more complex human research is, and the desperate lack of funding for olfactory research.

It seems that olfactory research has not been thought of as important even though research for our other senses is. Although we are really looking at fields of biology and psychology, this area is under-funded and could do with a boost. Perhaps it isn’t thought of as vital because people with olfactory disorders can still work and survive in society – or perhaps is seen as too frivolous and unnecessary. It doesn’t bode well for stronger studies in this area and Erox corporation will probably carry on doing quite well out of AND and EST.

Further on the topics discussed:

The Smelly Mystery of Human Pheromones TED talk

The search for human pheromones: the lost decades and the necessity of returning to first principles

MHC-correlated odour preferences in humans and the use of oral contraceptives

The Scent of a Man: to attract a woman by wearing scent, a man must first attract himself

Sexing up the human pheromone story: how a corporation started a scientific myth

Pheromones and Animal Behavior

How animals communicate via pheromones

Pheromone parties

Bombykol

Disclaimer & credits

Any mistakes in this text are mine. Getty Images pictures used under their free embed scheme. Sorry about the ads you might see below (this blog is hosted on the free WordPress servers). This post is based on Dr. Tristram Wyatt’s talk at the Royal Society of Chemistry, arranged jointly by the British Society of Perfumers and Society of Cosmetic Scientists.

The British Society of Perfumers Annual One Day Symposium was held at Whittlebury Hall in Towcester again this May and had an accidental theme of fragrant roots – with two of the presentations focusing on a different kind of scented root accord unbeknownst to one another. One of the suppliers, Albert Vieille, also went beyond scent and served us delicious macaroons flavoured with essential oils of neroli, rose and mandarin which were perfectly accompanied by the Arabica Coffee Salvador alcoholic extract we smelled alongside them.

The British Society of Perfumers Annual One Day Symposium was held at Whittlebury Hall in Towcester again this May and had an accidental theme of fragrant roots – with two of the presentations focusing on a different kind of scented root accord unbeknownst to one another. One of the suppliers, Albert Vieille, also went beyond scent and served us delicious macaroons flavoured with essential oils of neroli, rose and mandarin which were perfectly accompanied by the Arabica Coffee Salvador alcoholic extract we smelled alongside them.